- 고래의 약탈을 막아라

ZACK THE RIPPER

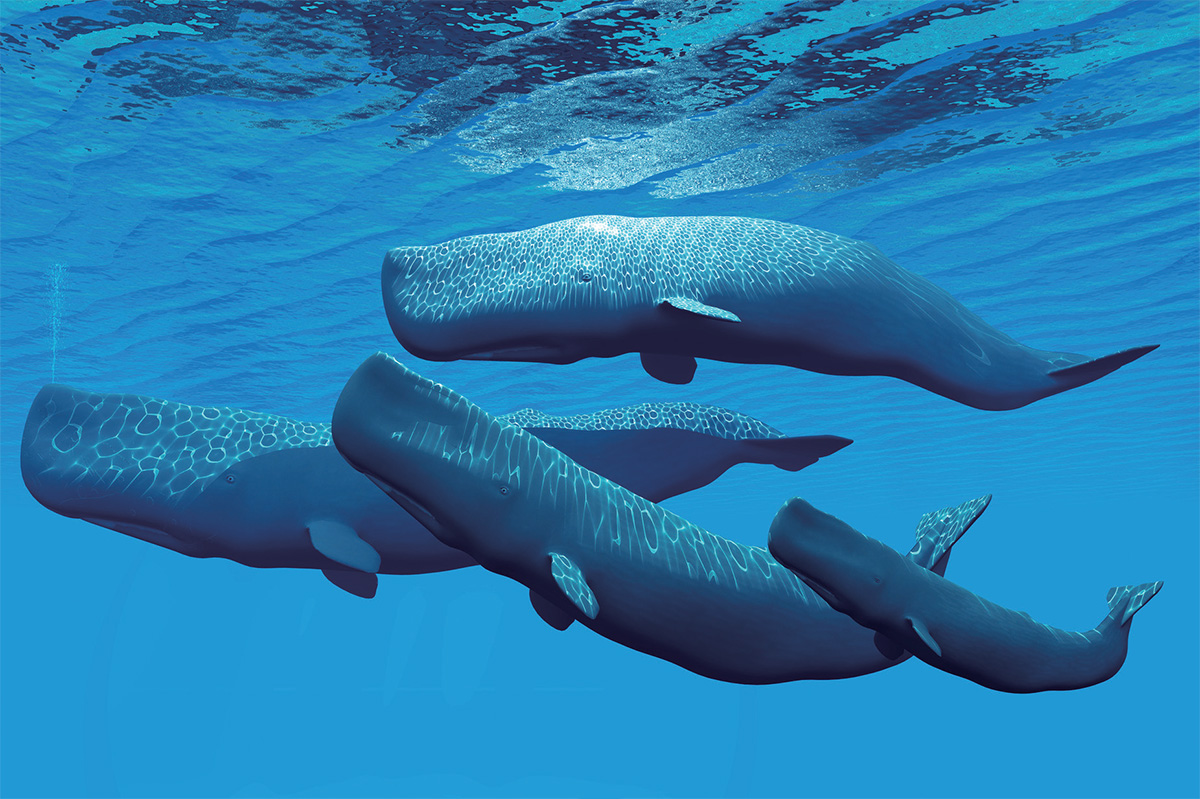

Alaskan fishers are teaming up with scientists to protect their catch from crafty, thieving sperm whales.For longline sable fishers in the Gulf of Alaska, there are few omens of doom more chilling than the enormous shadow of a whale approaching their boat. That’s because in the past several years, male sperm whales, the lone wolves of the ocean, have been behaving strangely. They have been teaming up to hunt fish right off fishers’ hooks, and every year more whales are coming to eat from the fishing line buffet, leading some scientists to speculate that they’re somehow communicating about the richness of the hunting ground and sharing tips. They’re destroying thousands of dollars’ worth of fishing gear, altering the population of sablefish and endangering their own lives with the chance of getting caught in lines.

It all started about 20 years ago, when the sable fishing season was extended from one or two weeks to eight months. Previously, the season was so short that sperm whales swimming in and out of the Gulf of Alaska hunting for food didn’t have enough time to learn the habits of the fishers. Back then, depredation, the scientific term for when animals go around plundering food, wasn’t a problem. But just five years after the season extension, the whales had become so adept at hunting off the longlines that fishers were starting to panic.

Since then, it’s only gotten worse, says Linda Behnken, a 30-year commercial fishing veteran and executive director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association. Today, Behnken and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council estimate that the costs of the damage to vessels targeted by whales, and the extra time and bait that go into attempting to meet fishers’ quota after losing their catch, add up to more than $1,000 per ship, per day. “Most fishermen that have experienced whale depredation will tell you that [estimate] is low,” she says.

Sablefish typically live 2,400 to 3,600 feet below the surface. To catch them, fishers spend six to 12 hours traveling 15 to 90 miles offshore. Once they arrive, they lay their lines. The longline generally runs about 3 miles, with an anchor on one end to attach it to the seafloor and a buoy on the other so the fishers can find it at the end of the day. Along the line, there will be somewhere between 1,000 and 4,000 hooks, with bait on each one. Boats typically set two lines at a time, which sit for 12 hours. Fishers haul in the lines using hydraulics, and one crew member will typically stand on the boat’s rail and pull each fish off the hook as it comes out of the water. When no whales are present, a line with 2,000 hooks on it will typically catch 500 to 1,000 fish.

But when the whales are around, says Behnken, the fishing is miserable. “The catch can be easily one-quarter of what you would expect, and if you have enough whales on you, they can clean you out,” says Behnken. “They are usually taking turns going down and getting fish. When you finish hauling, they’ll all come up to the surface. Last year, one came right next to the boat and rolled. He was looking right at us. Maybe he was looking to see if there was more coming.” On one trip, her boat had as many as six whales surrounding it, waiting for dinner. “You start having lines come up with fish that are bitten in half, and you can see the whale teeth marks.”

After years of this, Alaska’s fishers reached out to a team of scientists for help. Quickly, a group formed: the Southeast Alaska Sperm Whale Avoidance Project, or SEASWAP, a collaboration among fishers, academic researchers, field scientists and both local and national government agencies. But deterring the sperm whales has proved to be much harder than anyone anticipated.

In part, it’s because sperm whales are not well understood, despite being one of the most famous of the ocean’s mammalian hunters. Scientists do know they’re the largest of the toothed whales and are easy to identify thanks to their giant, square-shaped heads and long, pointed lower jaws. Their blowholes are set at an angle off to the left side of their heads, and they use a series of clicks and echolocation to communicate and identify prey. For the most part, they eat squid (about a ton per day), and some speculate they may even find themselves in regular battles with giant squid, as it’s not uncommon for them to be found with large, suction-cup-shaped scars.

But beyond that, we don’t know much. Sperm whales are very difficult to study because they dive deeper than any other great whale — more than 5,000 feet — and once they get down there they can stay submerged for up to 50 minutes before they surface for air, miles away from their initial dive spot. So there were really no clues as to how the whales were finding the boats just as the fisherman were reeling in their lines. “Generally, what happens is the guys go out, they set their gear, let it soak for several hours and then pick it up. The whales won’t be around until they’re hauling the gear back. How do they recognize this thing that’s become the dinner bell?” asks Russ Andrews, a marine biologist with SEASWAP.

To answer the question, Aaron Thode, a marine mammal acoustic specialist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, set up passive listening devices on moorings to see if the whales or the boats were making unique noises when the lines were reeled in. What they discovered was that the sound of the bubbles created by the revving of the propellers as the boat sped up and slowed down during the line-reeling process was calling the whales.

“It wasn’t a piece of equipment; it was the way they handled the vessel,” says Thode. “We finally convinced ourselves by going out on a vessel without gear. We put the engine into gear, and in less than 10 minutes we had 40-foot whales around the vessel.” From their acoustic research, the team learned that the whales can hear this dinner bell from 3 miles away in stormy weather and up to 17 miles away on a clear day.

The next step was to understand how many whales were down there and how exactly they were eating, so the team attached underwater cameras to the fishing lines. “The most experienced whales learned they could bite the line and cause it to shake—like shaking apples off trees,” Thode says. “The fish have soft mouths, so [the whales] could shake the fish off the line, and they don’t have to risk getting their jaw caught on a hook.”

The takeaway was that there was little that could deter the whales. They’re too smart. Even attempts at playing a recording of the dinner bell sound from a decoy boat failed—the whales figured out that trick and went elsewhere for their meal. The team realized that deterrence was going to have to be replaced with a system of avoidance — figuring out where the whales were and alerting fishers so they could steer clear. So now begins the long and difficult process of attempting to attach satellite tags to the hunters so the fishers can know where they are and remain outside that 17-mile range of the whale’s hearing ability. Andrews has managed to tag about seven whales so far by standing on a small inflatable boat and shooting the tags at each whale with an air gun.

The fishers are also starting to get pretty good at visual identification. Sperm whales are easily differentiated by the markings on their tails, and SEASWAP’s co-leader, marine biologist Jan Straley, has been able to photo-ID about 150 of the whales that spend their time in the gulf. Of those, about 12 to 15 are the worst perpetrators — including one whale the fishers have dubbed Zack the Ripper. “He’s our bad boy,” says Behnken.

But having the data isn’t enough. To successfully avoid the whales, the fishers need to work together to get at least 17 miles away from the hunters. Though fishers are not in the habit of helping one another, Behnken says, she’s been able to convince them that every time a whale gets dinner, it’s receiving positive reinforcement. So using a combination of the satellite tagging maps and reports from fishers, Behnken and SEASWAP have been able to establish a makeshift whale reporting network.

Meanwhile, the team has begun collaborating with other fisheries around the world where depredation is happening on a smaller scale (a group at the Crozet Islands, a French territory in the Southern Indian Ocean, is having trouble with killer whales, for example). And other organizations are starting to pick up on the acoustic techniques that SEASWAP has pioneered. But most of all, the scientists say, they will be benefiting from the unique relationship the research has developed between the fishers and the scientists.

“There are researchers all over the world that are envious of our relationship with our fishermen,” says Straley. “They trust that what we’re doing is going to be better for them and the whales in the end.”

고래의 약탈을 막아라

알래스카만에서 주낙에 걸린 은대구 먹어치우는 향유고래…피해 줄이기 위해 어민과 과학자 손잡아알래스카만의 은대구 주낙 어민은 배로 접근하는 바닷속의 거대한 그림자만 보면 가슴이 덜컥 내려앉는다. 바다의 무법자 수컷 향유고래가 수년 전부터 희한하게 행동했다. 떼를 지어 달려들어 낚시 바늘에 꿰인 은대구를 포식한다. 낚싯줄에서 뷔페를 즐기려고 모여드는 고래가 매년 증가한다. 과학자들은 고래가 낚싯줄에 풍부한 먹이가 걸려 있다는 사실을 알고 서로 정보를 공유하는 게 아닌가 추정한다. 고래의 약탈은 어구를 망치고 은대구의 씨를 말린다. 그들 스스로 낚싯줄에 걸려 죽을 위험도 크다.

약 20년 전 은대구 낚시 시즌이 1∼2주에서 8개월로 길어지면서 그런 현상이 시작됐다. 이전엔 시즌이 짧아 알래스카만에서 먹이를 사냥하는 향유고래가 어민의 작업 패턴을 알아챌 시간이 없었다. 그땐 고래의 약탈이 문제되지 않았다. 그러나 시즌이 연장된지 5년만에 향유고래가 주낙에 걸린 은대구를 바로 잡아먹는데 아주 능숙해졌다.

30년 경력의 알래스카 주낙 어민협회의 전무인 린다 벤켄은 그 이래 상황이 악화됐다고 말했다. 북태평양수산관리위원회에 따르면 요즘 고래의 표적이 된 어선의 피해는 1척 당 하루 1000달러 이상이다. 어획량을 채우려다 보면 시간과 미끼도 더 많이 든다. 벤켄 전무는 “고래의 약탈을 겪은 어민이라면 실제 피해가 그보다 훨씬 크다는 사실을 잘 안다”고 말했다.

은대구는 해수면 730∼1000m 아래 서식한다. 주낙으로 은대구를 잡으려면 연안에서 25∼150㎞ 떨어진 바다로 나가 6∼12시간을 보내야 한다. 목적 해역에 도착하면 낚싯줄을 내린다. 주낙의 길이는 대략 5㎞ 정도다. 한쪽은 닻에 연결해 해저에 닿고 다른 쪽은 해수면의 부표로 이어진다. 줄 하나에 미끼를 꿴 낚시 바늘이 1000∼4000개 달려 있다. 주로 한 번에 두 줄을 내린다. 12시간 뒤 기계로 줄을 끌어올린다. 고래가 없다면 2000개 바늘을 단 한 줄에서 은대구 500∼1000마리가 잡힌다.

그러나 고래가 모여들면 작업을 완전히 망친다. 벤켄 전무는 “보통은 어획량이 예상의 4분의 1로 줄고 고래가 많을 땐 완전히 허탕칠 수 있다”고 말했다. “고래들은 차례로 내려가 바늘에 꿰인 은대구를 포식한다. 낚싯줄을 다 끌어올리면 고래들이 해수면으로 올라온다. 지난해 고래 한 마리가 배 바로 곁으로 올라와 몸을 뒤틀며 우리를 노려봤다. 은대구가 좀 더 올라올지 지켜보는 듯했다.” 한번은 고래 6마리가 배를 에워싸고 은대구가 올라오기를 기다렸다. “반쯤 물어뜯긴 은대구가 줄에 매달려 올라오기도 한다. 고래 이빨 자국까지 볼 수 있다.”

이런 일이 반복되자 알래스카의 어민은 과학자에게 도움을 요청했다. 곧바로 어민, 학계 과학자, 현장 연구자, 정부기관으로 팀을 꾸려 동남알래스카 향유고래 방지 프로젝트(SEASWAP)가 시작됐다. 그러나 향유고래의 약탈을 막기는 생각보다 훨씬 어려웠다.

우선 향유고래는 바다의 포유류 포식자로 가장 유명하다는 사실 외엔 별로 알려진 게 없다. 과학자는 향유고래가 몸집이 가장 크고 이빨이 있으며, 거대한 사각형 머리와 길고 뾰족한 아래 턱 덕분에 식별이 쉽다는 사실은 안다. 분수공이 머리 왼쪽으로 기울어졌으며 흡착음과 음파 위치 측정법을 사용해 상호 소통하고 먹이를 식별한다. 대부분 오징어(하루 약 1t)가 주식이다. 향유고래의 몸 표면에서 거대한 빨판 형태의 상처가 자주 발견되는 것으로 봐서 대왕오징어와 자주 싸우는 게 분명하다.

그러나 그 외엔 과학자들도 잘 모른다. 향유고래는 다른 어떤 대형 고래보다 더 깊이 잠수(1500m 이상)해 최대 50분 동안 머물 수 있으며 입수한 곳에서 수㎞ 떨어진 곳에서 부상하는 습성 때문에 연구하기가 매우 어렵다. 따라서 어민이 낚싯줄을 올릴 때 고래가 그 배를 어떻게 찾아내는지 알 수 없다. SEASWAP의 해양생물학자 러스 앤드루스는 “고래는 낚싯줄을 끌어올려야 모여 든다”고 말했다. “고래가 그것이 식사 시간을 알리는 소리라는 사실을 어떻게 알까?”

그 의문을 풀기 위해 캘리포니아대학(샌디에이고 캠퍼스) 스크립스 해양연구소의 해양 포유류 음향 전문가 에어런 소드는 수동 음탐기를 설치했다. 낚싯줄을 올릴 때 고래나 어선이 특이한 소리를 내는지 알아보기 위해서였다. 그 결과 낚싯줄을 끌어올리는 과정에서 어선이 속도를 냈다가 줄일 때 프로펠러의 회전이 만들어 내는 거품 소리가 고래를 불러들인다는 사실을 발견했다.

소드는 “낚싯줄을 올리는 게 아니라 배의 움직임이 신호였다”고 말했다. “낚싯줄 없이 실험했을 때 배의 속도를 높였다가 줄이자 10분도 안 돼 거대한 고래들이 배를 에워쌌다.” SEASWAP 팀은 음향 연구를 통해 고래는 그런 소리를 폭풍이 칠 땐 5㎞ 밖에서, 맑은 날엔 27㎞ 밖에서도 들을 수 있다는 사실을 확인했다.

그 다음 고래가 몇 마리나 모여들며 어떻게 은대구를 먹어 치우는지 알아보기 위해 낚싯줄에 수중 카메라를 설치했다. 소드는 “가장 노련한 고래는 낚싯줄을 물어 흔든다”고 설명했다. “나뭇가지를 흔들어 사과를 떨어뜨리는 것처럼 말이다. 그래야 낚시 바늘에 고래의 턱이 꿰이지 않는다.”

결론은 고래가 너무 영리해 은대구 약탈을 막을 방법이 거의 없다는 것이었다. 위장 보트에서 녹음한 소음을 틀자 고래가 알아채고는 다른 곳으로 가버렸다. SEASWAP 팀은 고래의 위치를 사전에 알아내 어민이 그 장소를 피하도록 하는 방법뿐이라고 판단했다. 그에 따라 고래가 소음을 듣지 못하게 배를 고래로부터 27㎞ 밖에 있도록 하려고 고래에 위성 확인이 가능한 색인을 부착하는 길고 고된 작업이 시작됐다. 앤드루스는 고무보트를 타고 공기총을 사용해 지금까지 고래 7마리에 색인을 부착했다.

어민의 육안 확인 기술도 발전했다. 향유고래는 꼬리로 쉽게 식별할 수 있다. SEASWAP의 공동 팀장 잰 스트랠리는 알래스카만에 서식하는 고래 약 150마리의 모습을 촬영했다. 그중 12∼15마리가 약탈을 가장 즐긴다. ‘잭 더 리퍼’로 이름 붙인 고래를 두고 벤켄 전무는 “그 녀석이 가장 흉포하다”고 말했다.

그러나 데이터 확보만으론 충분치 않다. 고래의 피해를 막으려면 어민이 서로 연락해 고래로부터 최소 27㎞ 떨어져야 한다. 벤켄 전무는 어민이 원래 서로 잘 돕지 않지만 그들을 설득해 고래가 나타날 때 서로 알려주도록 했다. SEASWAP은 위성 색인 지도와 어민의 보고를 종합해 ‘고래 발견 보고’ 네트워크를 만들었다.

SEASWAP 팀은 다른 나라 어업 기관들과도 협력한다. 예를 들어 남인도양 프랑스령 크로제 제도의 어민도 소규모지만 범고래의 피해를 입는다고 보고했다. 다른 기관들도 SEASWAP이 개발한 음향 기술을 도입하기 시작했다. 그러나 무엇보다 어민과 과학자의 긴밀한 협력이 가장 중요하다.

스트랠리 팀장은 “전 세계의 연구자가 우리와 어민의 협력 관계를 부러워한다”고 말했다. “어민은 우리가 하는 일이 자신과 고래에게 도움이 된다고 확고히 믿는다.”

- ERIN BIBA NEWSWEEK 기자 / 번역 이원기

ⓒ이코노미스트(https://economist.co.kr) '내일을 위한 경제뉴스 이코노미스트' 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지

![면봉 개수 → 오겜2 참가자 세기.. 최도전, 정직해서 재밌다 [김지혜의 ★튜브]](https://image.isplus.com/data/isp/image/2025/12/21/isp20251221000019.400.0.jpg)

![갓 잡은 갈치를 입속에... 현대판 ‘나는 자연인이다’ 준아 [김지혜의 ★튜브]](https://image.isplus.com/data/isp/image/2025/11/21/isp20251121000010.400.0.jpg)

당신이 좋아할 만한 기사

브랜드 미디어

브랜드 미디어

침묵 딛고 희망으로…돌아온 ‘제야의 종’, 2026년 맞았다

세상을 올바르게,세상을 따뜻하게팜이데일리

일간스포츠

일간스포츠

'변호사 선임' 다니엘, 어도어 431억 손배소 대응

대한민국 스포츠·연예의 살아있는 역사 일간스포츠일간스포츠

일간스포츠

일간스포츠

침묵 딛고 희망으로…돌아온 ‘제야의 종’, 2026년 맞았다

세상을 올바르게,세상을 따뜻하게이데일리

이데일리

이데일리

[마켓인]“연말 휴가도 잊었다”…‘상장준비’ 구다이글로벌에 증권가 ‘사활’

성공 투자의 동반자마켓인

마켓인

마켓인

장기지속형 대세론에 제동, 비만치료제 주 1회·경구 지배 전망…업계 시각은

바이오 성공 투자, 1%를 위한 길라잡이팜이데일리

팜이데일리

팜이데일리